It’s a depressing experience. You spend hours polishing the perfect mix. But when you hear it in the car, or on a friend’s system, or in a club, it sounds all wrong. The low end is overwhelming, or completely undercooked. The top end is harsh and brittle, or perhaps too soft and muted. The vocal that sat so well in your studio is inaudible, or way out front. And the mid-range that you spent so long working on suddenly feels boxy, or hollow, or tinny.

The obvious response is to blame your loudspeakers. But good studio monitors are expensive — and there’s no guarantee that replacing them will solve your problems. A better understanding of the problems themselves will help you to avoid wasting money on a speaker upgrade that might achieve nothing.

In The Room

Loudspeakers are never heard in isolation. They radiate sound in all directions, and it bounces off our walls, ceiling, floor, desktop, and everything else in the room, reaching our ears by multiple paths of different lengths. We never hear the pure sound of our speakers on its own. It’s always combined with reflected sound.

That, in itself, is not a bad thing. Real-world listening also takes place in rooms with walls and floors, so it makes sense to mix in a similar environment. But it means we need to consider the environment and the speakers together as a complete system. And the factors that make mixing difficult often have much more to do with the room than with the speakers.

That’s especially true of problems relating to the low frequencies, which are the most difficult monitoring problems to fix. If you remember your high school physics, you’ll recall that there is an inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength. The speed of sound in air is 343 metres per second. So, at a frequency of 343Hz, the wavelength is one metre. The lower the frequency, the longer the wavelength, so for example at 100Hz, the wavelength will be 3.43 metres. Why is this significant?

It matters because the dimensions of a typical room are also within this range. If our studio is 3.43 metres from side to side, we can fit exactly one cycle of a 100Hz sound wave between them, or exactly half of a 50Hz wave. And what happens in this case is that playing a bass-rich tone will set up what’s called a standing wave. We won’t hear 100Hz at the same level everywhere in the room. Instead, the room will contain hot spots where it’s far too loud, and nulls where it cancels out completely. Our speakers might have a perfectly flat frequency response, but if we happen to be sitting in a 100Hz null, that frequency will sound much too quiet.

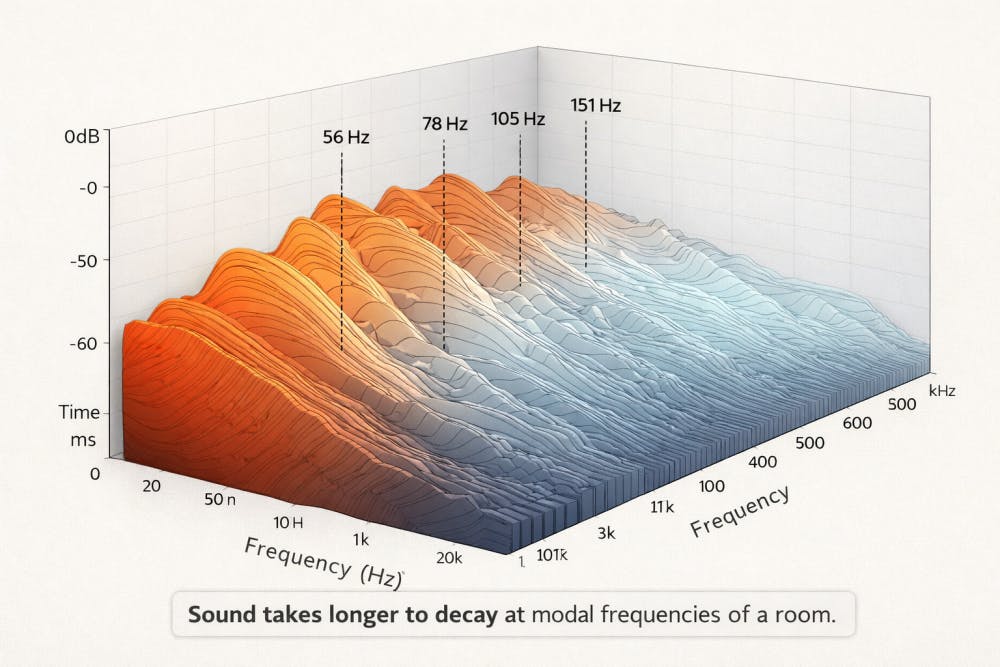

It gets worse, because rooms don’t just have two walls. They have at least four, plus a floor and a ceiling. And the distances between all of these opposing surfaces all correspond to wavelengths for frequencies in the 80Hz-200Hz region. Not only that, but standing waves can also form along longer paths that connect more than two surfaces, and at multiples of the lowest resonant frequency. The icing on the cake is that these resonances also ‘ring’. Sound takes longer to die away at these frequencies than it does at others.

Beast Modes

The frequencies at which standing waves form are dictated by the dimensions of the room. Collectively, they are known as the room modes. You can find out more about room modes and standing waves by reading this blog entry [https://www.sonarworks.com/blog/learn/room-modes]. The crucial thing for our purposes is that the problems they cause can’t be solved by changing your speakers. If the bass response at your listening position is uneven, you’ll need to address it through acoustic treatment, by moving to a different room, listening in a different position, or relocating the loudspeakers.

When you can’t hear low frequencies clearly enough, the temptation is often to upgrade to bigger speakers, or to add a subwoofer. But unless you also tackle the real origin of the problem, you will most likely make things worse, not better, by putting more bass energy into the room. If it’s not feasible to move to a different space, or install effective acoustic treatment, you will benefit more from buying a good pair of open-backed headphones instead.

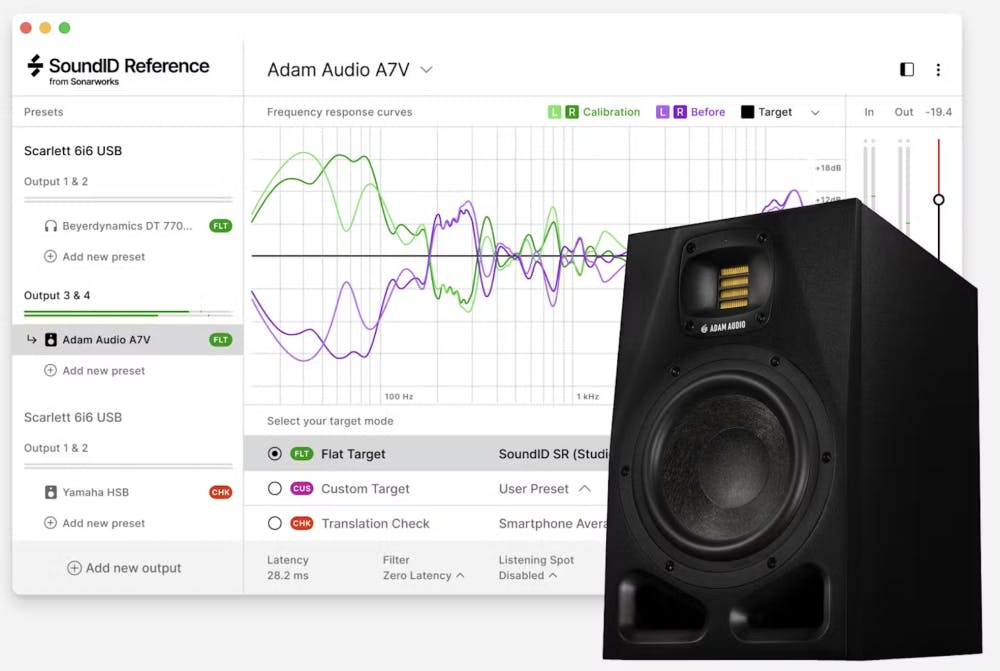

Can speaker calibration help? Up to a point. A calibration system such as Sonarworks’ SoundID Reference works by measuring the sound at the listening position, calculating the ways in which it deviates from the ideal response, and applying equalisation to compensate. If there is a 100Hz hot spot at the listening position, it can reduce the amount of 100Hz that enters the room in the first place. But if there is a null at 100Hz, pumping more of that frequency into the room will have minimal effect. And software equalisation cannot alter the way in which resonant frequencies take longer to decay than they should. When room modes are causing bass drums to sound like an extended ‘boom’, rather than a short, sharp ‘thud’, calibration won’t fix it.

On Reflection

Above 300Hz or so, room problems are caused by reflections rather than standing waves. These problems can take several forms. If too much of the sound reflected back to the listener arrives at exactly the same time, we’ll hear it as a distinct echo. This is the sort of effect you get if you clap your hands whilst standing under a bridge, or in a tunnel. It’s entertaining when you’re going for a walk, less so if you’re trying to mix.

The surfaces that reflect sound also change its character. When sound encounters a hard surface such as a tiled or plastered wall, very little of it is absorbed. By contrast, carpets and curtains tend to absorb high frequencies, whereas lower frequencies pass through and are reflected by the hard surfaces behind them. Specially designed acoustic panels can absorb sound down to relatively low frequencies, and are therefore the main tool for controlling standing waves.

As well as controlling the low frequencies, a good mix room needs to contain an appopriate balance of absorptive and reflective surfaces. Too much high-frequency absorption, and the sound in the room will be dark and muddy. Too little, and it will be distractingly bright and splashy. It’s also important to control the overall amount of reflection in the room. If we kill all the reflections, our room won’t be representative of real-world listening environments any more. But if there’s too much reverberation, or if it takes too long to die away, we won’t be able to hear the direct sound from our speakers clearly enough.

Again, it’s important to understand that issues caused by the room can’t be solved by changing the speakers. If your mixing space is too lively and reverberant, that’ll be a problem with all loudspeakers. The best solution is to improve the acoustics within the room, and the good news is that this is usually much easier with midrange and high frequencies than it is at the low end. Even if you’re working in a domestic bedroom or a rented space where you can’t attach things to the walls, it should be possible to make a difference with inexpensive DIY treatment.

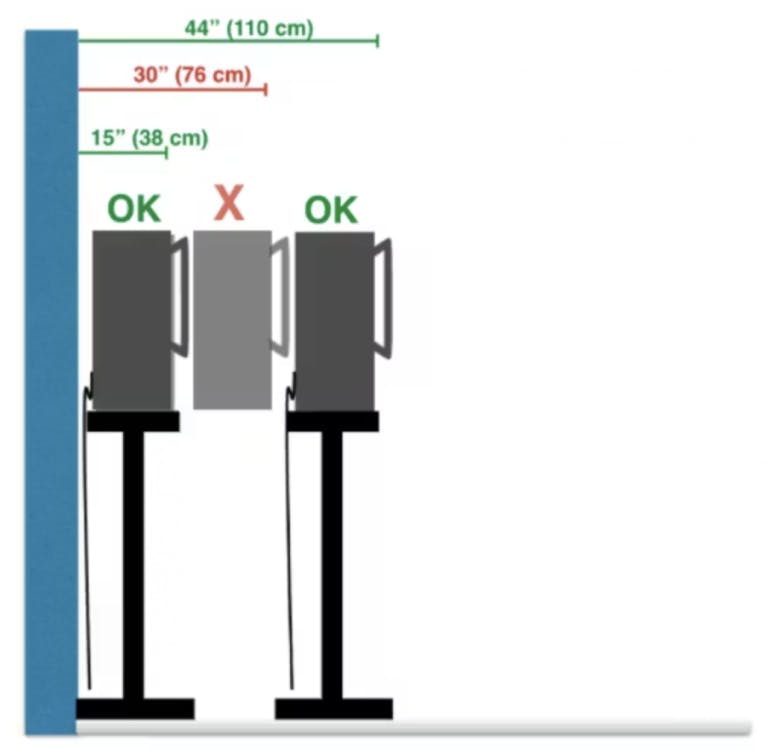

You can also make a difference by fine-tuning the placement of the loudspeakers in the room. Assuming the room is rectangular, the speakers should usually be placed along one of the shorter walls, so that they are pointing down the long dimension of the room. They should not be in the corners, but they should be arranged as symmetrically as possible, and usually, as close to the wall as is feasible.

Once you’ve optimised the speaker position and treated the room, you’ll be able to improve the sound still further with calibration. Unlike with room modes at the low end, equalisation is an effective way to address an uneven frequency response in the midrange or high end.

Back To Bass

As we’ve seen, understanding the interaction between loudspeaker and room is fundamental to achieving good results. To mix stereo, we need two speakers. To mix immersive or surround sound, we may need as many as 12. Ideally, all of our speakers will interact with the room in a similar way, but in practice, that’s rarely the case, because the position of the speaker within the room makes a big difference. This gets very complicated with immersive audio, but even in stereo, speaker placement is important.

Placing a speaker near a solid wall introduces an effect called speaker boundary interference response (SBIR). At low frequencies, speakers are not very directional: they radiate sound not only towards the listener, but outwards at all angles. Sound emanating from the back of the loudspeaker is reflected from the wall behind it, and arrives at the listening position marginally later than the sound emanating from the front of the speaker, which reaches us directly. The reflected sound interferes with the direct sound, causing some frequencies to be boosted and others to be attenuated. Which frequencies are affected depends on how far the speaker is from the wall, but again, the problem usually arises somewhere in the 80-300 Hz region.

By adjusting loudspeaker placement, we can sometimes use this to our advantage, for example by counteracting the influence of some room modes. Alternatively, placing the speakers very close to the wall, as suggested above, raises the frequencies that are affected into the range where they are most easily tackled using acoustic treatment. But it’s also easy to see how the wrong loudspeaker placement can make things worse.

For example, if your speaker is exactly the same distance from two or three solid surfaces — as it would be in the corner of a room — problems due to SBIR are multiplied. And if your speaker placement is not symmetrical, so the two speakers are different distances from nearby walls, the frequencies affected will differ from one speaker to the other.

Once more, these issues can’t be solved by buying more expensive loudspeakers. But you can make a difference by experimenting with the placement of your existing monitors. And, unlike room modes, SBIR can be tackled effectively through calibration.

Skill Issues

Unsatisfactory mixes aren’t only down to bad monitoring. Andy Wallace or Serban Ghenea would deliver a better mix from a bad environment than most of us could produce in the best control room. Talent and experience have a huge role to play here, but so too does the raw material. Professional mixers get to work on projects recorded by the best engineers, in the best studios. The best mixers will take these to the next level, but they already sound good by the time mixing begins. That’s less often true of home productions.

There is often more to be gained by working on your own skills than by spending money upgrading speakers. Try to track down professionally recorded multitrack projects and practice on those. Consider enrolling in a course or hiring someone to teach you. Think critically about arrangment and choice of sounds before you start on a mix.

When To Upgrade

So, why do expensive loudspeakers exist, if upgrading won’t solve your problems? Are there any benefits to be gained from buying new speakers, and if so, what are they?

The starting point is important here. If you’re currently working on the speakers built into your laptop, or cheap multimedia desktop speakers, then you’ll certainly notice the benefits of upgrading to a pair of purpose-designed studio monitors. A system that’s not capable of putting across the full frequency range, or which distorts appreciably, is not good enough to mix on in any room.

However, if you’re already using a decent pair of modern, full-range active monitors, costing say Ђ500, the benefits of upgrading to another pair of modern, full-range monitors costing twice as much might be limited unless you’ve put the time and effort into optimising your room acoustics and listening position. It would be like buying a Custom Shop Fender Strat and playing it through a cheap practice amp.

Affordable active monitors today offer performance that’s often better than the pro-level speakers of 30 years ago. Unless you are very unlucky, Ђ500 should get you something that’s easily loud enough for home studio use, with plenty of extension at both ends of the frequency range, and distortion levels low enough to be unnoticeable in normal use. So what might you get if you spend more money?

For one thing, it’s now common for active loudspeakers to incorporate digital signal processing, which can be used to implement room calibration. Although you can do this with software such as the SoundID Reference plug-in, there are practical advantages in having the calibration ‘baked in’ to the loudspeakers. Models such as ADAM Audio’s A-series are able to host SoundID profiles directly in the speaker, simplifying the computer setup and eliminating the risk of bouncing a mix through the calibration plug-in by mistake. That’s a significant practical benefit that may well justify the cost of the upgrate.

The Power Of Three

Another possibility is that you might be able to upgrade to a three-way system, or to a 2.1 setup with a separate subwoofer. Whereas headphones just have one driver per side delivering the entire signal, loudspeakers usually divide up the frequency range, allowing a larger and more powerful driver to handle the lower frequencies whilst a smaller ‘tweeter’ puts out the highs. However, this involves some design compromises. It’s hard to make a low-frequency driver that can deliver solid bass whilst also being clean through the midrange. Also, the ‘crossover’ region where sound is handled by both drivers tends to fall in a frequency range where our ears are particularly sensitive, so any coloration it introduces can be audible, especially if you’re not directly in front of the speaker. Introducing a third driver that’s dedicated to the midrange allows the bass driver and the tweeter to be more tightly optimised for their roles, and although it introduces an extra crossover, the crossover frequencies in a three-way speaker are often more benign.

Adding a subwoofer to a two-way system can have some of the same benefits, taking the load off the bass driver and extending the frequency range at the low end. And whereas the main speakers should be set up to form an equilateral triangle with the listener at the third corner, a subwoofer can be positioned elsewhere in the room, which may help with room modes. However, unless this is done with care, and your room acoustics are well controlled, the extra low-frequency extension can cause more problems than it solves.

More expensive speakers typically use better components, which can improve reliability and overall performance. And spending more money is likely to give you a wider choice of speaker technologies. For example, coaxial loudspeakers mount the tweeter in the centre of the midrange driver, rather than above it. Implemented well, this can improve stereo imaging and off-axis response. Likewise, almost all affordable monitors employ a hole in the cabinet called a reflex port. This serves to enhance the bass response, but at the cost of what’s called ‘group delay’: in essence, you get more bass, but it tends to lag behind the rest of the sound. If you’re able to spend more money, you can choose alternative designs such as sealed-box or transmission line speakers. None of these designs is free of compromises, but the compromises are different!

To sum up, if you are currently mixing on a set of speakers that’s not intended for the purpose, you probably should aim to switch to some purpose-designed monitors. But if you’re already mixing on a reasonably good set of monitor speakers, and struggling to get the results you want, it will pay to ask yourself a few questions before you spend thousands on an upgrade that might disappoint:

Is there an alternative space available that might sound better?

What are the options for acoustic treatment in my room?

Is room calibration likely to help?

Are there better choices for speaker and listening position?

Can checking my mixes on headphones make a difference?

What can I do to improve my own mixing skills?