Binaural audio monitoring is transforming how producers work with headphones and speakers. Walk into any studio today, and you’ll see monitors at the front, headphones on the desk, and producers alternating between the two. For decades, we’ve treated these as fundamentally different tools. Now, with binaural audio monitoring technology using personalized HRTFs and virtual room simulation, the line between them is rapidly disappearing. Technologies like Virtual Monitoring Pro from Sonarworks are bridging this gap, making binaural audio monitoring the future of professional production.

To understand the new era of monitoring, we need to start with a deceptively simple question:

Why do speakers feel real, and why do headphones feel like sound is trapped inside your skull?

The answer lies in the physics of acoustics, and our brain interprets spatial cues. Let’s look at how we hear sound around us, how speakers differ from headphones, and how we can reproduce the sound of speakers on headphones.

How Your Brain Hears a 3-D Soundfield: The Science Behind Spatial Hearing

Your auditory system is a subconscious 3-D rendering engine. In any environment, it decodes tiny timing differences, frequency coloration created as sound passes around the physical shape of your head and into your ears. It also takes into account the early reflections and decay time of the room. When listening to speakers, your brain merges these cues into a 3-D acoustic image of the soundfield.

A few key principles are at play here, so let’s define what’s actually happening:

Interaural Time Difference (ITD)

A sound arriving slightly earlier at one ear indicates its direction—left, right, or somewhere in between. These microsecond-level timing differences are the primary cues for horizontal localization. This is how we can close our eyes and still pinpoint the location of a sound source.

Interaural Level Differences (ILD)

When a sound comes from one side, your head partially blocks it from reaching the opposite ear. This “head shadow” attenuates the sound, especially at high frequencies, creating a level difference the brain interprets as direction. Imagine standing near a lamp. One side of your face is brightly lit, while the other is in shadow. Your ears experience the same effect with sound.

Spectral Cues

Your head and outer ear (pinnae) change the frequency spectrum of sound as it arrives due to diffraction, reflections, and resonances. Sound from different directions is tonally altered in a way that allows your brain to define its directionality. Your brain has learned over time how to decipher the frequency spectrum as it relates to the position of sound.

Reflections, Room Cues, and Psychoacoustic Glue

Beyond the direct sound, your brain uses reflections (the first 5–35 ms of room bounce) to anchor a source in space, while also defining the size and shape of the space around you. The brain can differentiate between the original (first) sound and the secondary reflections that the room creates. These reflections create a sense of the room’s size and shape, as well as the location of a sound in the room. This can be compared to viewing an object vs its shadow. We see both things, but our brain understands which shape is the original object and which is the shadow. The shadow gives us clues about the size and location of an object.

Head-Related Transfer Functions (HRTFs): Your Personal 3-D Audio Fingerprint

The brain decodes all of the above phenomena to describe the space around us and the acoustic path from a sound to your ear canal. Each person’s unique physical attributes define how their brain processes sound. This processing model can be mathematically represented with a Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF)

How We Process Stereo Music Over Stereo Loudspeakers

Stereo loudspeakers produce a soundfield with natural space and depth because both ears hear both speakers. Your brain automatically decodes timing, level, and tonal cues to build a 3-D soundstage in front of you—an experience fundamentally different from headphone listening. A few principles describe why speakers sound natural.

Both ears hear both speakers

Each ear receives sound from both channels. The left ear clearly hears the left speaker, but it also hears a weaker, filtered version of the right speaker. These ITD, ILD, and spectral balance differences between the ears create what we commonly refer to as crosstalk or crossfeed. This acoustic crosstalk is the foundation of realistic stereo and the reason speaker listening feels externalized and believable.

Panning and the Phantom Center

When a signal plays from both speakers at the same level and phase, your brain fuses them into a center image—even though no physical speaker exists there. This phantom center is the anchor of stereo reproduction. The center image “floats” in front of you between the speakers. Panning a sound across a mix creates slight time (ITD) and level (ILD) differences between the speakers, which tricks your ears/brain into visualizing a sound somewhere between the speakers.

Early reflections create depth and room identity

A mix may contain ambience that was captured during the recording, and probably spatial effects were added during mixing. The speakers reproduce this sound into your listening environment, and then the listening room adds its own early reflections and decay time to the playback. So, when listening on speakers, we are hearing a combination of the ambience embedded in the source, plus the ambience added by the room. This isn’t much of a problem because we are used to this phenomenon, and other listeners will experience a similar result, shaped by their own environment. It’s easy to see that music mixing studios should have well-controlled reflections and decay times so that the ambience of our mix room doesn’t overly affect our mix decisions.

Room modes shape low-end clarity

Similarly, the low frequencies produced by our speakers interact with the boundaries of our room, causing peaks and dips in the frequency response. It is imperative that, when listening to speakers in a mix room, the room produces a flat and accurate low-frequency response. If the room is influencing what we hear, we can’t predict how our mix will translate to other playback systems. As you’ve probably experienced, low-end translation is the most room-dependent aspect of music mixing and mastering.

The Room Causes the Speaker to Lie to You

We’ve all experienced mixes that sounded great in the mix room but not so great in other locations. This is likely caused by a room problem, not a speaker problem. Virtually every professional speaker can produce a flat frequency response when measured in an anechoic chamber. Still, for the end user, the room has a significant influence on what we hear. This means that when mixing on speakers, especially in an unfamiliar or untreated room, it is very likely that our mix will not translate well to other playback systems.

Armed with this knowledge, perhaps we should just use headphones….

How We Process Stereo Music Over Headphones

With headphones, each channel goes directly to its corresponding ear, resulting in no crosstalk, no room sound, and none of the added filtering from your head and outer ears. Without those cues, your brain has a hard time building a natural 3-D soundfield, so the soundfield feels detailed but also “inside your head.” The phantom center sits right between your ears instead of floating in front of you, panned elements feel extra wide or vague, and the sense of depth mostly disappears because there are no reflections to indicate distances. And since your personal HRTF isn’t really engaged, localization feels a bit more abstract and less like what you’d hear over speakers in a room.

This same isolation also benefits us while monitoring on headphones due to a heightened sense of detail, low-level resolution, and immunity to room interference. Headphones are excellent for editing, detecting noise, and judging reverb tails, especially when working in untreated spaces. But the limitations are equally real. Decisions about spatial imaging, frequency balance, and mix depth can be misleading. Center elements may seem too forward or too loud, leading to translation issues for speakers. Headphones are great for detail, but not so great for realism. What to do?

Binaural Audio to the Rescue

Binaural audio is the technology that makes headphones sound as if you’re listening to speakers in a room. “Binaural” simply means that left and right signals have been processed to recreate the acoustic cues your ears receive from real-world sound sources, by simulating HRTFs, interaural timing, interaural level differences, and crosstalk.

Additionally, binaural room simulation adds simulated room reflections to enhance realism and to create a more externalized, speaker-like image. The phantom center appears in front of you, with panned elements floating naturally between the “virtual speakers,” and depth and ambience are implied from the simulated room reflections. With effective binaural processing, headphones can approximate how stereo mixes translate on loudspeakers, reducing the issues that normally make headphone mixes unreliable.

For binaural processing to sound effective, the mathematical model of how we hear, our HRTF, must be applied to the sound signal. In practice, there are two methods for generating an HRTF: generic or personalized.

Generic HRTFs use an average head and ear shape—essentially a “one-size-fits-most” model. For some people, they can create a convincing sense of width and some degree of externalization. However, because the spectral details don’t match your unique anatomy, your brain doesn’t fully recognize the cues as its own. The result can feel slightly vague and ambiguous. Generic HRTFs often produce a pleasant but somewhat flattened or internalized binaural image.

Personalized HRTFs, on the other hand, use your actual ear shape, head size, and torso geometry, usually captured through listening tests or ear scans. When the binaural filters match your anatomy, your brain instantly “locks onto” the cues, producing dramatic realism. The soundfield feels natural and immersive, panning is sharply defined, and elevation and front-to-back placement become clear. The phantom center sits naturally in front of you, and the whole image feels stable and speaker-like. With personalized HRTFs, the binaural impression becomes not just spacious but also represents the localization model that your auditory system has learned over a lifetime

For producers, this means that binaural headphone monitoring can behave like real speakers.

The Virtual Studio

If we measure our personalized HRTF using speakers in a room that we trust and enjoy listening in, we can create a binaural representation of that listening environment for headphones. Then you can take your favorite room with you wherever you go, just using headphones. Your room—with your headphones!

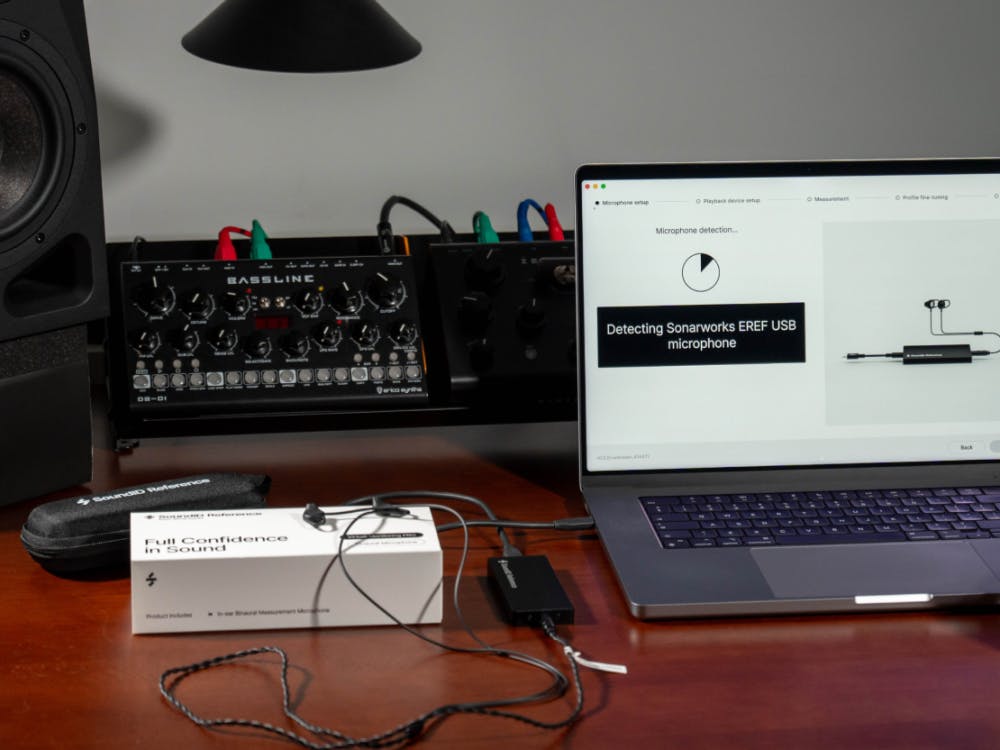

Sonarworks has been in the business of calibrating speakers and headphones to create accurate monitoring. And now you can address exactly this issue of translating any room you can measure onto any over-the-ear headphone you prefer. This system is called Virtual Monitoring Pro, and can be achieved by anyone.

Virtual monitoring measures your personalized HRTF over speakers with a pair of microphones placed in your ears. Then it measures the HRTF with the same microphones, but through over-the-ear headphones. Using these two HRTFs, SoundID Reference can create a custom profile that accurately represents the sound of the speakers over the headphones.

The speaker measurement should be made on a system that you trust. It could be your calibrated control room, your vehicle system, a commercial studio that you have access to, or a friend’s room. The headphones you choose should be quality, professional headphones, but they needn’t be expensive. There are some excellent headphones at every price point.

Virtual monitoring over headphones provides consistent, calibrated monitoring wherever you choose to work or listen. It eliminates the headphone-specific anomalies previously causing headphone mixes to sound unpredictable over speakers.

The Future of Monitoring

We’re entering a new era where binaural audio monitoring is personalized, adaptive, and increasingly intelligent. We can easily create personalized HRTFs that provide a realistic sense of a natural environment over headphones through binaural audio monitoring technology. This will allow more accurate mixes that translate properly to different playback devices. This system is scalable, eventually supporting not only stereo but also immersive formats.

We’ve spent decades arguing over “headphones vs. speakers,” but that debate no longer makes sense. We can now confidently make decisions on speakers and headphones, check our mix in a virtual club environment, and even audition a soundbar or car stereo. Monitoring becomes fluid, dynamic, and personalized—rather than locked to a single pair of monitors in a single physical room. Speakers will never disappear. Headphones will never replace a great room.

But together, powered by personalized acoustics and virtual environments, they’re giving producers a more honest picture of their mixes than ever before.