Phase is one of the most misunderstood terms in audio. We all know that phase is a thing. We know that it can be shifted, and that when things sound bad, phase is sometimes the cause. But learning a little more about it can make a huge difference to our recordings and our mixes.

What Is Phase?

When multiple sounds happen at the same time, they combine to form a single sound. Our ears and brain can identify the constituent parts, but the air pressure at any given point in space can only ever have one value at a time. The same is true of the electrical voltage generated by a mic, or a sample in a digital audio file.

This works in the other direction, too. We hear a guitar or a voice as being a single sound. In engineering terms, however, it is a complex sound. The mathematician Charles Fourier showed that any continuous waveform can be broken down into multiple sine waves at different amplitudes and frequencies, just as the text on this screen is actually an arrangement of individual pixels. The sine wave is the building block out of which other sounds are constructed.

DAWs represent a sine wave as a repeating series of curves, alternately above and below the centre line. When two sine waves at unrelated frequencies are combined, we just get a more complex waveform. But what happens when the two waves are at the same frequency?

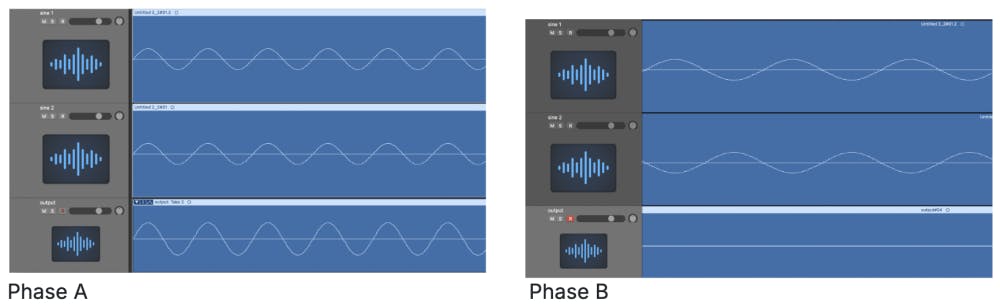

Visualise two 1kHz sine waves displayed one above the other in a DAW. When these are lined up perfectly, they are said to be in phase. Now, let’s slide one of them exactly half a wavelength to the right, such that the crossings are in the same place, but one goes above the line whilst the other dives below it. In this case, the two are said to be out of phase. The phase relationship or angle between two such signals is expressed in degrees. When they’re perfectly in sync, the phase difference is zero degrees (or 360, or 720…). When they’re out of sync, it’s 180 degrees. And, of course, the it can be anywhere in between.

Why does this matter? Because combining two sine waves with the same frequency doesn’t create a more complex waveform. Instead, we still get a sine wave at the original frequency, but louder or quieter. If the two sine waves were equally loud to start with, and are perfectly in phase, the amplitude will be doubled. This is known as constructive interference or reinforcement. But if the phase angle is 180 degrees, we’ll get a flat line: complete silence. This is known as destructive interference or cancellation.

Changing Phases

In the real world, we don’t work with pure sine waves. Moreover, real-world sounds aren’t continuous. They get louder and quieter over time, and they change in pitch and timbre. It’s highly unlikely that combining two sounds from different sources will lead to total silence. But if two sounds are similar, there can nevertheless be audible reinforcement or cancellation at some frequencies. This is the origin of phase problems. It’s also the basis of some common audio effects.

Consider what happens if we duplicate a complex waveform such as a guitar part onto a second track in a DAW. When we play back both at the same time, all of their constituent sine waves will be perfectly in phase at all frequencies. The timbre and the waveform will be the same, it’ll just be twice as loud.

Now suppose we slide one of these audio regions slightly to the right in our DAW, or use a plug-in to apply a 1 millisecond delay. Suddenly, we have changed the phase relationship between original and duplicate — and, crucially, we’ve changed it by a different amount for every frequency. A 1ms delay represents a full wave cycle at 1kHz, so there will be constructive interference at that frequency. But at 500Hz, a 1ms delay is equivalent to half a cycle, and we’ll get cancellation. So, although we’ve combined two identical sounds, the resulting output has some frequencies reinforced and others attenuated. (By slowly varying the delay time, we can change the frequencies at which this happens and obtain the shifting effect known as flanging.)

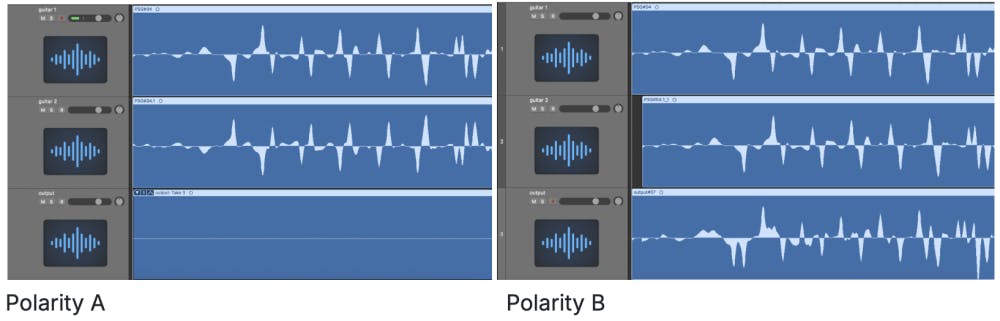

Flipping Out

Now imagine that instead of creating a time difference between the original and duplicate waveforms, we turn one of them upside down. Reversing the waveform in this way is known as changing its polarity, and combining the initial sound with a polarity-reversed version of itself leads to complete silence. However, reversing polarity is not the same as applying a 180-degree phase shift — except in the special case where you’re dealing with pure, unvarying sine waves at the same frequency. With anything else, there is no time offset that will lead to destructive interference at all frequencies. Polarity and phase are related, but they are not the same.

In The Real World

Both phase and polarity are sources of real-world problems. These arise either when we capture the same sound in multiple ways, or when the same sound is played back more than once.

On the recording side, take the common example of a guitar amp miked with both an SM57 and a ribbon mic. Our ribbon mic has a figure-8 polar pattern, and in isolation, it will sound the same whichever way around it is. However, turning the mic round has the same effect as reversing the polarity; so when we combine it with the SM57, everything that’s in common between the two signals will cancel out, and the combined sound will be very thin.

Figure-8 mics also have a lot of proximity effect, so we might want to move the ribbon mic further from the amp to make it less boomy. However, it’s then hearing the amp fractionally later than the SM57 up against the grille, creating a phase difference. When we blend the two, some frequencies will now be reinforced and others will be cancelled. The combined sound of the two mics faded up together will no longer be halfway between both, but significantly different from either. By careful listening and mic placement, we might achieve a great guitar sound that wouldn’t have been possible with one mic. But if we just throw both mics up without listening to them together, we might equally find the results are thin and gutless.

Phase and polarity issues arise often when recording a drum kit. It’s fairly common to mic up both the top and bottom of the snare drum, with one mic pointing down while the other points up. This means that the snare sound is captured in opposite polarity on the two. Since the top and bottom snare sounds are different to start with, they won’t fully cancel, but there can be enough cancellation to make the combined snare sound quite thin. Elsewhere, when two mics are ‘hearing’ the same drum from different distances, the resulting phase differences can also change the tone in ways that aren’t desirable, for example when the overhead mics are combined with the close mics.

Another situation where phase issues are almost inevitable is when miking a singing guitarist or pianist. The voice unavoidably spills onto the guitar mic, and vice versa. By itself, that spill might not sound too bad. But when the two mics are faded up together, the phase relationship between the vocal mic and the vocal spill on the guitar mic can cause obvious problems.

Solving Phase Problems

The best way to solve phase and polarity problems is to avoid them at source. The oft-misunderstood 3:1 rule can be a useful guide here. A rule of thumb rather than a law of physics, this states that if two mics are capturing the same source from different distances, phase problems can be avoided if the more distant mic is at least three times further away than the closer mic. Following the 3:1 rule usually ensures the two signals are sufficiently different to combine relatively benignly, though you should always check with your ears.

Mixer input channels usually have a button labelled with the ø symbol, which reverses the polarity of the signal. This can help in situations where two mics are picking up the same source in opposite polarity. And, as phase and polarity are related, it can also sometimes help address phase problems. If we’re combining two signals that are similar enough to reinforce each other at some frequencies and interfere destructively at others, swapping the polarity of one will reverse this effect. Frequencies that were previously being reinforced will now be attenuated, and vice versa.

No matter how much care you take at the tracking stage, phase problems sometimes reveal themselves at the mix, whether it’s because of a different balance, EQ setting or some other change. One thing that can make a difference here is time-alignment, whereby very short delays are used to adjust the phase relationships between individual signals. For example, if the DI signal from a bass guitar doesn’t sound good when combined with the miked amplifier, you can try delaying it by a couple of milliseconds. Some manufacturers also make processors known as phase rotators. These typically use something called an all-pass filter, which is in effect a frequency-dependent delay. Compared to the original signal, this produces an output that has different degrees of phase shift at different frequencies.

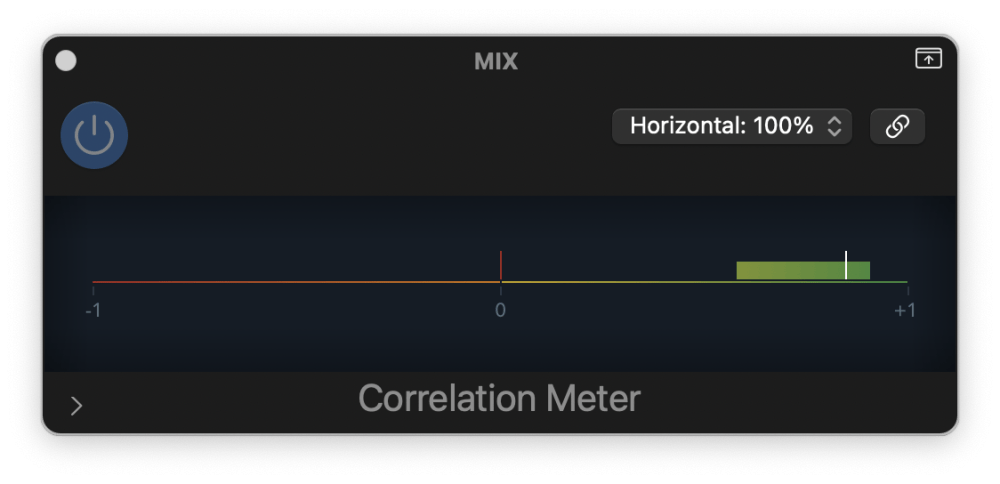

Finally, a word of warning. If you find you have two tracks that don’t combine well, it can be tempting to manage this by panning one to each side. Indeed, this can make the mix feel excitingly wide, but be careful. Your mix will inevitably be heard on mono systems sooner or later, so dealing with phase problems by panning is a sticking plaster, not a solution. A good way of checking stereo content for phase problems is to use a correlation meter.

This should read somewhere between +1, as you’ll see with a mono mix, and zero, which is what you see when the left and right signals are completely unrelated. A sustained negative value indicates significant out-of-phase content in your stereo mix.

Continue exploring and reading about: