The art of mastering appears shrouded in mystery, but the ever-evolving role of the mastering engineer is not hard to understand and today, more than ever, almost anyone can learn how to master audio and decide for themself whether or not what they’ve created is ready for release.

Historically, mastering engineers evolved from “cutting” or “transfer: engineers, who were responsible for transferring recordings from tape to vinyl. The work of cutting engineers focused mainly on optimizing the audio so that a vinyl disc could play reasonable quality audio without the needle skipping off the record. That is, the cutting engineer focused on the technical issues of disc cutting rather than creative issues. The 1980s ushered in the compact disc and digital mastering with almost unlimited audio processing capabilities. The role of the mastering engineer began to include not only corrective processing but also creative changes to an audio file as it is prepared for distribution and mastering became relied upon as a step needed to finish a project sonically.

Today, mastering is as much a technical process as a creative one, and in this blog, we’ll break down the role of the mastering engineer, how it’s changed over the years, and why it’s more important than ever to have your tracks mastered on a well-tuned monitor system.

The History of Mastering

In the early days of recording, there were no specialized roles—a single engineer oversaw the entire recording process from start to finish. Early recordings were created by simply placing one or maybe a few microphones in front of a live band. The band was balanced in the room and the result was cut directly into a wax or acetate disc, which was then used to create a stamper for 10-inch shellac or vinyl records that played at 78 RPM.

In 1948 Ampex produced the Model 200 tape recorder and “transfer engineers” became experts at transferring recordings from tape to a vinyl master for reproduction. In 1954, the Recording Industry Association of America standardized the frequency response of playback devices with the introduction of the RIAA equalization curve as the de facto global industry standard for vinyl records. This curve ensured a flat frequency response from vinyl records and reduced the amount of high-frequency noise at the expense of emphasized low-frequency rumbling. Since bass-heavy recordings could cause problems with the stylus jumping out of the groove, engineers began to apply corrective EQ during the vinyl-cutting process to create better-sounding and more reliable records.

This was the beginning of modern mastering — when the role of the mastering engineer shifted from a purely technical process to a creative one. It was during the 1950s that engineers like Steve Hoffman made a name for themselves by enhancing masters with creative tools like EQ and compression. Hoffman was known for his work with jazz artists, including Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, and The Beach Boys.

Stereophonic Sound

In 1968, Sterling Sound became the first studio in the US to cut stereo discs, which opened up a whole new creative world for transfer engineers, who could now affect stereo width, frequency balance, and dynamics. These engineers’ responsibilities included not only transferring audio recordings from one format to another but also improving fidelity in the process. As engineers made more and more creative decisions, the term “transfer engineer” eventually gave way to “mastering engineer.”

Bob Ludwig, one of the most well-known and perhaps the first independent mastering engineer, began his career in the 1960s and has mastered projects by more than 1,300 artists, resulting in over 3,000 credits, more than 25 Grammy nominations, for artists ranging from The Rolling Stones and Queen to Def Leppard and Coldplay. He has mastered recordings on virtually every analog and digital recording format for every major record label and he continues to operate out of his facility, Gateway Mastering, in Portland, Maine.

Going Digital

The compact disc’s 1982 debut caused one of the largest disruptions in audio we’ve ever seen: the adoption of digital audio, which advanced the mastering engineer’s role even further. Digital audio production was pioneered by companies including AMS, Waveframe, Fairlight, and New England Digital, along with the Apple II, Atari ST, and the Commodore computers. In 1989, Digidesign, which became part of Avid, released the first version of the industry-standard Mac-based Pro Tools software, called Sound Tools, making digital audio production available to studios of every size.

Digital audio formats offer improved dynamic range and a greater signal-to-noise ratio over analog formats while also allowing mastering engineers to increase the perceived loudness of a track. Artists and labels quickly discovered that listeners (and radio programmers) perceived a louder version of a track to sound better so labels began requesting louder and louder masters—usually at the expense of musicality, dynamics, and distortion.

The Loudness Wars

The competitive practice of creating loud masters has been around since the 1950s, and journalist Greg Milner identifies 1994 as the year in which “there was no turning back” for the Loudness Wars. By 1999 it had gotten so bad that many of the top-selling albums had almost no dynamics, leading some engineers to call it “the year of the square wave.” Digital mastering allows for more extreme peak limiting and louder average levels than analog mastering leading to modern records being, on average, about 18 dB louder than in 1980. Raising the average level of a master is not necessarily a bad thing, but overprocessing a recording often results in unpleasant artifacts, such as distortion and a lack of musical dynamics.

Dynamic Range Day created by mastering engineer Ian Shepherd brings awareness to how the Loudness Wars affect the enjoyment of music and honors musical releases that exhibit notable dynamic range. Shepherd charted the average loudness of some of the most popular records from the last 20 years. Shepherd found that Metallica’s Death Magnetic (2009) is perhaps the loudest album ever created, with an average dynamic range of just 3dB (from peak to RMS). For reference, Metallica’s The Black Album (1991) has a dynamic range of 11dB. Streaming services normalize the loudness of their playlists and therefore discourage the practice of creating extremely loud masters, so the loudness wars have cooled off a bit over the past decade.

Modern Mastering

Self-releasing music is possible for more artists and creators than ever, but digital distribution requires expertise in a range of ever-evolving topics. While almost anyone can develop the skills to successfully create great-sounding mixes and distribute the files through an aggregator, it’s wise to enlist a mastering engineer with the expertise and experience to optimize your music for distribution. Mastering engineers take responsibility for not just the sonics of your music, but the proper encoding of the files. There are four key areas that mastering entails.

First, mastering engineers have the opportunity to shape the sonics of the final product, correcting any frequency imbalances, optimizing the dynamic impact of the recording, and ensuring that a particular song, album, or playlist competes artistically with the rest of the world. This step requires a keen ear, top-shelf audio processors, respect for the intention of the artists involved, and most importantly, an accurate monitoring environment to ensure that the master sounds great everywhere.

Second, mastering engineers provide the final quality control step before distribution. The audio files are carefully examined for technical flaws ranging from sloppy edits to noises and artifacts that may have been created or amplified during production, mixing, and mastering. Many artists distribute their own music, making the quality control aspect of mastering particularly important. Nobody wants to release a song with a glitch, like an embarrassing click, pop, or cut-off ending. Once a song has been released, it’s virtually impossible, and potentially costly, to remove a file from the internet.

Third, all creators should be credited and paid for their content and the collection and distribution of royalties is tracked through metadata embedded in the digital files. Mastering engineers know how to best embed that metadata and can advise the artist or label on what data should be generated and tracked for different types of digital releases.

Lastly, distribution today encompasses audio formats from vinyl and CD to streaming platforms to video games to immersive and multichannel audio formats. Masters for each format require specific attention to file encoding and delivery requirements. Multichannel audio brings with it a whole new set of problems and solutions that require almost daily attention to the updated specifications of each device and platform.

Self Mastering

Mastering and releasing music by yourself is always an option and a lot can be learned from the resources available from sites like Ian Shepherd’s Production Advice site and Izotope’s “Are You Listening” YouTube channel. There are also many excellent books and online material about mastering from Jonathan Wyner, Bob Katz, Bobby Owsinski, and of course the Sonarworks blog.

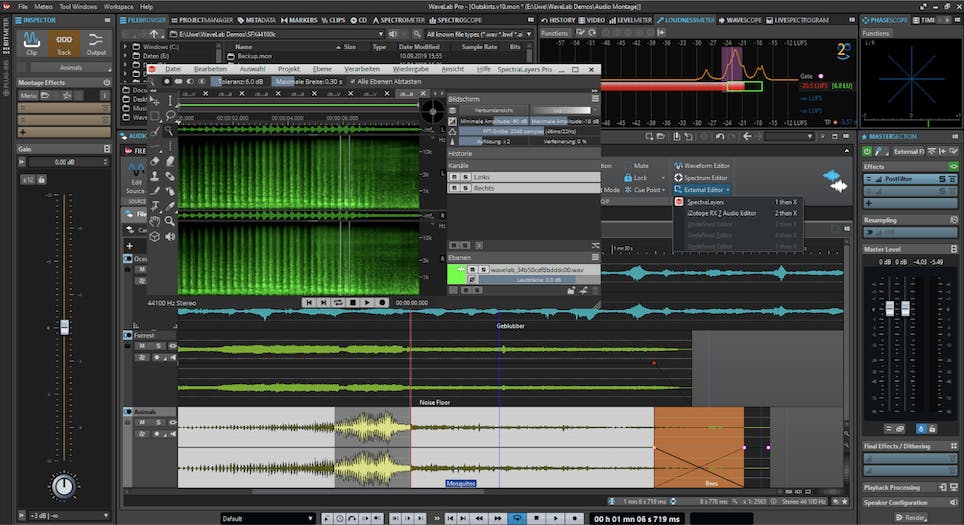

Professional tools for digital mastering come from just about every plugin manufacturer and virtually every DAW is capable of creating professional-quality audio. Mastering programs, like Steinberg Wavelab and Presonus Studio One (in Project mode) provide workflows for embedding metadata, creating files for distribution, specialized metering, and even proprietary plugins. These programs speed up the mastering workflow and automate some of the tedious aspects of mastering.

Keep in mind that the most important aspect of mastering your own music is your monitoring environment. You must be able to trust your headphones or studio monitors to provide a flat and accurate representation of your music, or you won’t be able to create masters that sound good everywhere. SoundID Reference software ensures that your monitors and headphones are as accurate as they can be.

Mastering is not mysterious or secret but encompasses a highly specialized set of tools and skills that have developed over the last century. It would benefit any producer or mixer to learn as much as possible about the art and science of mastering so that the best decisions can be made while preparing a project for release.

Continue reading our other articles about mastering:

How to prepare a mix for a mastering engineer

Pro mastering tips: compression, multiband compression, and mid-side compression.