The Shift: Headphones as a Primary Mixing Tool

Mixing exclusively on headphones was once a last resort. Today, it’s a choice and not just for bedroom producers. Major releases like Billie Eilish’s When the Party’s Over and Bon Iver’s i,i were mixed largely on headphones, proving that portable monitoring can deliver radio-ready results.

Yet anyone who’s been burned by a mix collapsing on speakers knows the challenge: headphones present sound in a way your brain doesn’t encounter in the real world. The solution isn’t to force them to behave like speakers – it’s to understand the psychoacoustic differences and design a workflow that closes the translation gap.

The Psychoacoustic Gap and Why It Matters

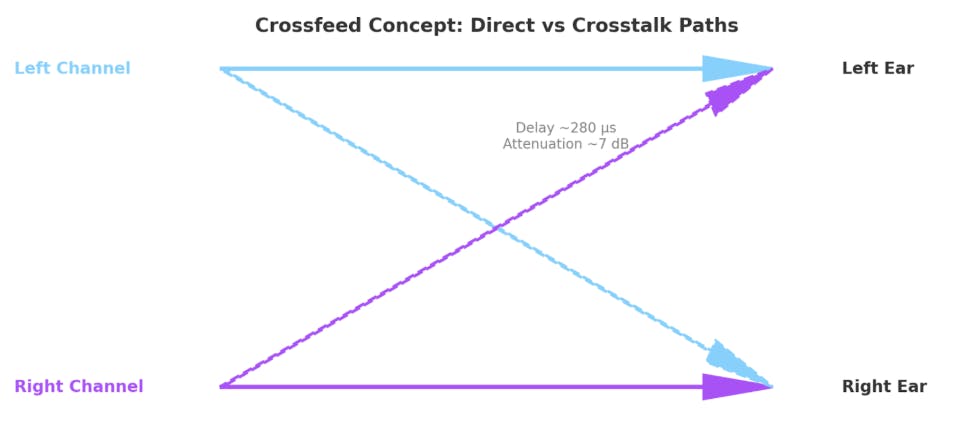

Speakers feed both ears with both channels. This acoustic crosstalk gives your brain location, depth, and spatial width cues. Headphones bypass that entirely: left ear hears left channel, right ear hears right. The result?

- Stereo width feels artificially wide.

- Centre elements feel locked in place.

- Reverb and ambience seem exaggerated.

These differences can tempt you into mix decisions that don’t hold up in speaker playback. The fix starts with reintroducing those missing cues in a controlled way.

Step 1: Controlled Crossfeed: Science Over Guesswork

Crossfeed often gets a passing mention in mixing discussions – and Sonarworks’ How to Pan Like a Pro on Headphones touches on its role – but it’s one of the most powerful tools for closing the gap between headphone and speaker perception. Let’s look at how to use it with intention.

- Crosstalk between ears in speaker listening typically arrives 270–300 μs later than the direct signal and about 6–9 dB quieter.

- Crossfeed plug-ins emulate this delay and attenuation, restoring natural localisation cues and preventing overly wide imaging.

Advanced move:

- If you’re using SoundID Reference’s Virtual Monitoring, you can further refine translation by pairing it with a dedicated crossfeed plug-in. Start with a crossfeed delay around 280 μs and attenuation of 7–8 dB for open-back headphones; tighten slightly for closed-backs to avoid smearing transients.

- These parameters are not built into Virtual Monitoring itself — they must be set in your chosen crossfeed plug-in.

- Re-tune these settings by ear for each headphone model, then save them as part of your template session for consistency.

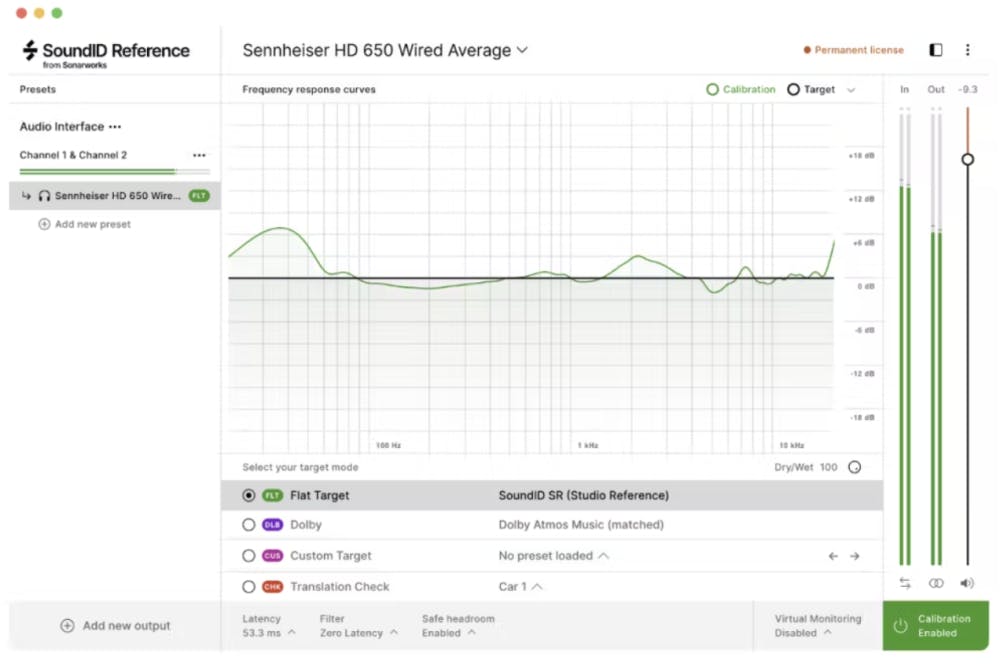

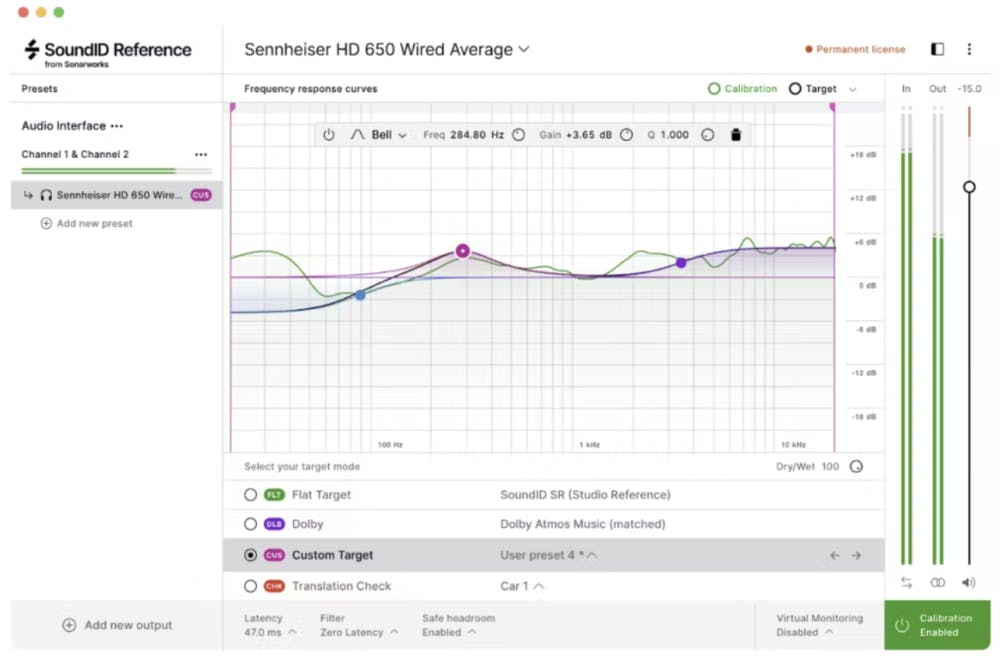

Step 2: Calibrate Beyond “Flat”

Most posts about headphone mixing focus on flattening frequency response. That’s step one, but for real-world translation, treat calibration as a dynamic tool:

Load your profile in SoundID Reference and mix in “flat” mode for 80% of the session.

For the remaining 20%, toggle through secondary curves “consumer”, “club”, or a deliberately mid-forward target to preview how your balances shift.

Log your observations: if your low mids consistently blow up on club curves, that’s a recurring bias you can pre-correct.

Over time, this translation log (a Glenn Schick–inspired mental map) becomes a running record of recurring discrepancies between your mix decisions and how they actually sound in other environments. By spotting patterns in these notes, you can identify consistent biases in your monitoring chain or mixing approach, then proactively adjust your workflow and settings in future sessions to correct them before they become problems.

Step 3: Reference with Intent

Reference tracks are already a staple, but the way you use them on headphones matters:

- Build a reference check playlist of 6–8 tracks in different genres, all of which you know inside-out on speakers.

- Level-match them to your mix to remove loudness bias.

- Drop them into your DAW and stream them outside your DAW through the same interface – the mental separation keeps you honest about what’s finished vs work in progress.

If you need inspiration, then head to this article that includes a list of sites where you can purchase high-resolution reference songs, or this one that lists 5 great reference tracks.

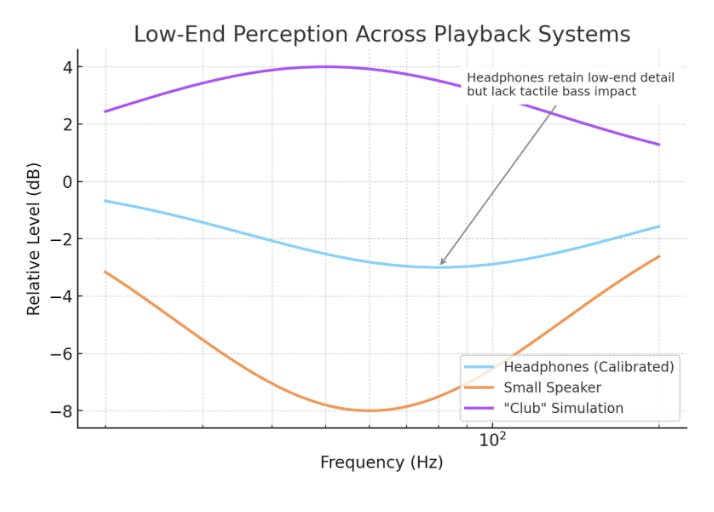

Step 4: How to Mix Bass on Headphones so It Translates to Speakers

Headphones can’t reproduce the tactile sensation of low frequencies coupling with your body in the way speakers do. That absence of physical feedback can cause bass to be under-represented or over-emphasised.

This visual makes it clear why bass decisions on headphones often don’t hold up elsewhere. Avoid guesswork by:

- Keep a low-frequency visualiser visible at all times for kick/sub relationships.

- Periodically switch to a small single-driver speaker or virtual laptop profile to check if bass is audible.

- Use Virtual Monitoring’s “club” preset, not for hype, but to reveal over-sub energy that would overload a PA.

Step 5: Workflow & Fatigue Management

Engineers adapt to context rather than sticking to one headphone type. Andrew Scheps values open-backs for their spacious sound in quiet environments, Katie Tavini switches between open and closed designs depending on focus and fatigue levels, and Glenn Schick uses IEMs when working on the move. The lesson? Build the agility to adapt your monitoring tool to your physical environment and preferences – that flexibility is just as important as any calibration curve.

Advanced fatigue-avoidance plan:

- Switch headphone type every 2–3 hours.

- Keep SPL at ~80–83 dB (eardrum equivalent) to reduce spectral skew from fatigue.

- Hard-stop every hour for 5–10 minutes of silence – not “scrolling” breaks, actual silence.

Step 6: Real-World Stress Testing Without Leaving the Desk

You don’t need to bounce, export, and run to the car anymore. Do it all in-session:

- Use Virtual Monitoring to switch between studio monitors, car speakers, and earbuds.

- Collapse your mix to mono and narrow stereo fields to mimic phone playback.

- Apply subtle bus limiting to check if mastering will alter perceived balance, then undo it before final export.

Step 7: Learn from the Ones Who’ve Done It at Scale

- Andrew Scheps: Loves the portability and detail but insists on one final pass on speakers for spatial decisions.

- Glenn Schick: Masters entirely on headphones, but only after building a mental translation map from thousands of projects.

- Katie Tavini: Warns against over-processing on headphones due to hyper-clarity; keeps the song’s “big picture” at the centre.

These philosophies have nothing to do with brand or model; they’re about workflow discipline and the ability to continually train your ears, refine your decision-making, and adjust your approach based on how your mixes translate over time.

Future-Proofing Your Headphone Mixing

The next wave of tools will go far beyond simple crossfeed:

- Personalised HRTF modelling will allow true speaker-accurate spatial rendering for your exact ears.

- Head-tracked binaural audio will dynamically adjust panning and depth based on head position, mimicking real-room shifts.

- AI-driven monitoring assistants will flag likely translation issues before you export, based on your personal mix history.

As this tech matures, the gap between headphone and speaker mixing will narrow to the point where translation becomes less about fixing and more about taste.

The Big Picture

The industry signal is clear: mixing on headphones has shifted from a fallback option to a mainstream professional workflow. Multiple respected engineers, including Blue May and TIEKS, report that 90–100% of their recent projects are mixed entirely on headphones, while others like Katie Tavini and MsM (Michalis Michael) describe a near 50/50 split with speaker use, leaning increasingly towards headphones for detail work and revisions. This trend is echoed across peer communities, where working mix engineers frequently report that headphones have become their primary mix environment, with speakers used mainly for spot checks.

With the tools, workflows, and engineer habits all converging on headphone-first production, developing a translation-ready headphone mixing process is no longer optional. By combining psychoacoustic precision, disciplined referencing, and adaptive monitoring strategies, you’re not just keeping pace with the shift, you’re positioning yourself ahead of where the industry is already working.

Take your headphone mixes to the next level with the SoundID Reference Virtual Monitoring – experience accurate studio monitor simulation on headphones with a fully functional 21-day free trial.