The art of mixing sound sources has been around a lot longer than most of us are aware of. In this lesson, Dashiell Hawkins dives in deep and reminds us that the placement of sounds we work with today has been played about with for centuries.

In Physics

Long before the advent of computers or even analog mixing consoles, composers were arranging sound sources in physical space, taking into account the properties of each instrument in an effort to create an overall balance. The loudest instruments would most often be placed along the back of the stage, to allow the solo instruments such as violins and flutes to cut through in the “mix”. It’s really quite fascinating when you draw the perspectives between the age old art of orchestra and modern music production – in fact there are a lot of techniques we can apply to our own mixdowns!

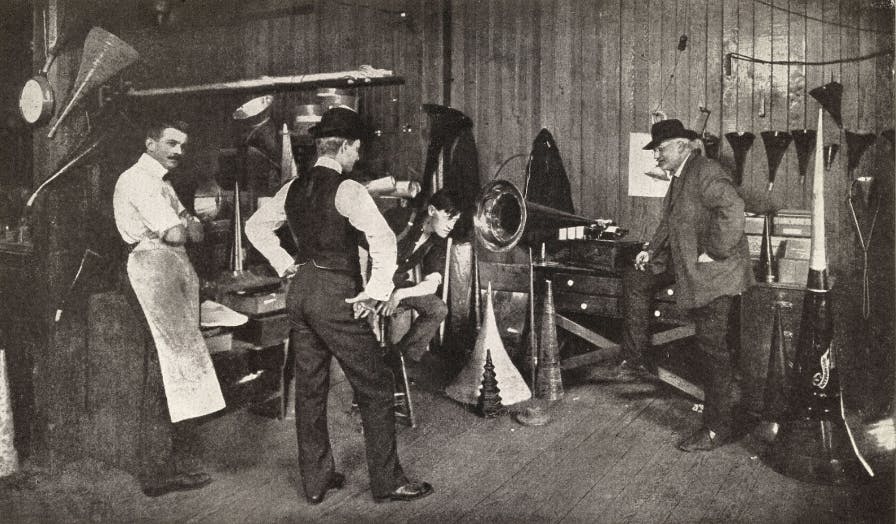

Similarly to how the composer places instrument to and from the front of the soundstage, modern producers use tools such as a reverb coupled with volume control to drown-out a sound source, and push it further back in the mix. In the very early days of recording, the equipment was limited and the invention of multitrack recording was still a futuristic concept.

Engineers would again make use of the space in which the recording was taking place, moving the instrumentalists around to make the most of the recording. When it was time for a solo, that musician would step towards the microphone to push themselves further forward in the “mix”.

Another very noteworthy technique in the placement of instruments in an orchestra that we can apply to modern music production is frequency conflict and separation.

You can easily apply an EQ and carve out a space for each sound to sit in the mix.

You know that feeling when you just can’t get your bass and kick drum to sit together in the mix without clashing? Imagine the days before EQ was invented, or before recording mediums came about! It’s common practice for composers to position the Double Bass section far-right of the stage while the Percussion or Timpani section is to the left of the centre-stage. This creates frequency separation and the technique can be seen used by producers to this day – hard-panning elements as to create a separate space in the mix for each of them.

Grouping similar elements in a mixdown is also common practice amongst audio engineers, it not only provides a much easier way to control multiple elements at once, but creates a more balanced sound overall – specifically when dealing with reverbs. Often audio engineers will use a single reverb in a project and make use of the send and return of either single channels or grouped elements, this creates a more realistic sound once all the elements are mixed back together. This technique is literally emulating the physical environment of that reverb, and making the most of placing your sound sources in their own space in that environment.

Since the advancements in recording and mixing technology, things have changed somewhat. Because stereo is common practice amongst audio engineers now and we have a lot more tools at our disposal, we’re able to achieve a lot of the same results with minimal effort. Instead of separating your kick and bass in the stereo field, and possibly create more phasing issues, you can easily apply an EQ and carve out a space for each sound to sit in the mix. Instead of moving a musician around in the studio while they’re performing in the hopes that you will get that one perfect take, you can simply duplicate the channel or apply automation. The key principles remain roughly the same.

The loudest sound will only truly sound loud if you have a soft sound beside it for the ear to relate

In Mathematics

Fibonacci is arguably one of the most important figures in the popularization of mathematics, not only is he responsible for presenting the works of Arabic mathematicians to Europe, he hypothesized the “Fibonacci Sequence” which is a proportional counting scheme that yields a very specific ratio. More popularly known as the “divine proportion” because of how widely it is echoed through nature from flower petals and pine cones to the proportions in human and animal bodies, in mathematics this ratio is known as “Phi”. Phi governs the relationship between adjacent numbers, the sum of the first two numbers will equal the third, the sum of the second and third numbers will equal the fourth and so-on – interestingly the ratio between the adjacent number will always equal Phi.

Most of the scales that western music utilize are based on natural harmonics which are created by ratios of the fundamental or root note and these ratios happen to line up perfectly with the first several numbers in the Fibonacci sequence so it’s safe to say it’s a pretty universal phenomenon. However without diving too much into the music theory let’s relate this concept to balancing elements in an audio mix, let’s say for example we have three sound sources, we mix the first two in at equal levels, to find a good balance between all three sources, the third would have to be louder than the first two.

Before you go and apply the ratio to all your mixdowns, it is very important to note that the art of mixing, much like any other art form – is subjective. Since the renaissance era, painters have been using the Fibonacci sequence to compose their paintings, while still leaving enough room for artistic license.

An acoustic guitar soloist recording and an EDM track are going to require a different approach to balance, however one thing that understanding these ratios has helped me with – is understanding the relativity of the mixing process. The loudest sound will only truly sound loud if you have a soft sound beside it for the ear to relate, this is the concept of Dynamic Range.

To sum it up

All-in-all, if you can take anything out of this – pay attention to the placement of your sounds as if they were in a physical space, use group channels and try cut down on the amount of reverbs you use in the mixdown process to create a more realistic environment. Start mixing in your key sound sources, the elements you want to cut through in the mix. When you have those at the desired level, then mix in your second layer of elements at the ratio described above and adjust to your taste. Then rinse and repeat the process, a truly dynamic mix has a distinguishable difference between the softest audible material and the loudest

Continue reading about phase issues, room modes, or browse through other topics.