Much like professional athletes train their bodies and stretch their muscles, audio professionals should hone and fine-tune their auditory skills. Every audio enthusiast has some ability to judge audio and recognize pleasant and dissonant sounds, but professionals need to go further and actually train their ears to quickly identify areas of interest and problem frequencies. Learning to recognize and put a name (or number) to frequency ranges or individual frequencies will aid us in production, mixing, and mastering.

Traditional Aural Training

Professional musicians study ear training to teach their ears and brain to decode music—allowing them to listen to music and recognize notes and chords in order to transcribe the music or play it back on their instrument. The ability to identify pitches and musical relationships is very important when transcribing and arranging music, and especially when conducting an orchestra or producing musicians.

For musical ear training, the teacher plays two or more notes on the piano while the student tries to name the notes or intervals based on a reference pitch. This is a great exercise for musicians, however audio engineers, mixers, and mastering engineers need to develop a sense of how frequency content is presented by an instrument or full mix. Engineers don’t have to specialize in arranging harmony, but we should specialize in understanding how the frequency balance of a sound or mix relates to the impact and emotional feel of a musical event.

Practice All The Time

I suggest that audio engineers start by listening to well-performed and well-recorded music. The genre doesn’t really matter, as almost all great recordings will provide a similar experience. Choose a song that really appeals to you and study it. Listen to it over and over and analyze what instruments are playing. When do new instruments enter and when does the arrangement thin out? What is the dynamic arc of the song? How loud is the loudest section and how quiet is the softest section?

Next, break down the song into musical frequency ranges—without defining the numerical frequencies of the ranges. What is creating the lowest rumbling? What creates the feeling of bass? What is punching you in the gut? Where does the lead instrument sit in the frequency spectrum? Where is the acoustic guitar? What instruments are playing chords and in what frequency ranges? What is playing counterpoint to the lead instrument/voice and in what range? What sounds are creating ambiance?

Once you’ve gotten this far, you will have gained a sense of how this music fits together. You should repeat this exercise for the rest of your life. I spend a few minutes each day listening to one or two new songs and going through this exact exercise. This training will not only remind you what music should sound like, but it will also highlight what is different about different playback systems. You’ll start to notice how different speakers and rooms present familiar music differently and you’ll start to recognize exactly what is different in each case.

“How can you bake a great-tasting cake if you’ve never tasted a great cake?”

Put Labels on It

As you work on music, isolate sounds and learn what frequencies exist in each sound. A spectrum analyzer can be helpful. Analyze each instrument to see what frequencies define its character. This may be slightly different in each song, but learn to put a number to rumble, boom, thickness, mud, forward mids, harsh mids, clear high-mids, harsh high-mids, silky top end, and harsh top end. Does a boomy acoustic guitar have too much 80 Hz, 250 Hz, or 400 Hz? Does a “honkey” vocal have too much 800 Hz, 1 kHz, or 3 kHz?

Some engineers find it useful to play pink noise through a 31-band graphic EQ and rais and lower each band to study what each range sounds like. A 31-band EQ provides three frequency bands per octave, which is actually a lot of resolution. A 10-band graphic EQ, like API’s 560, provides one band for each octave, which simplifies things a bit. API’s 550A and 550B EQ provide 19 to 26 preset frequencies for you to practice on. Of course, sweepable parametric EQs let you hunt for any possible center frequency.

You should get to the point where you can distinguish between 50 Hz and 100 Hz and maybe eventually between 50 Hz and 75 Hz. In fact, bass frequencies are much easier to differentiate than high frequencies, as bass octaves cover only a few dozen Hertz (20 Hz to 40 Hz), while treble frequencies can cover thousands of Hertz (10 kHz to 20 kHz).

Many well-known mixers and mastering engineers don’t think in terms of note names or specific frequencies, but their brain is accurately discerning which instruments and sounds occupy critical frequency ranges. Keep in mind that music is about emotion and a frequency that produces mud in one song may produce warmth in another.

Tools for Practice

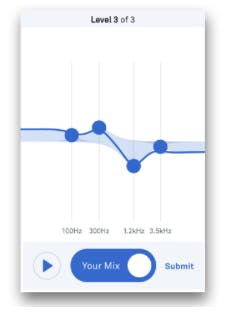

While spending time critically listening to music and sound systems will train your ear and brain, specific tools and methods have been designed to expertly focus your training. One such tool (from Sonarworks) is an ear training exercise disguised as a game called Match the Mix. This game helps hone your skills at recognizing differences between two versions of a mix. Your task is to create an EQ curve to match the two mixes.

There are many paid and free online ear training tools. I recommend checking out iZotope’s (free) Pro Audio Essentials site for their EQ practice exercises. These sophisticated exercises take you through simple to complex equalizer challenges. The Quiztones Mac and iOS Apps are designed to help engineers develop their listening skills.

Besides just listening for frequency content, you should learn to recognize different types of distortion, plosives, sibilance, background noise, and phase problems. Each of these is a subject to itself, but learning to recognize these types of issues will improve your productions and mixes and will also let you assess the performance of speakers and headphones.

Often we have to work in unfamiliar environments and on unfamiliar speakers. Bring along some music that you are familiar with and listen to your music in the new environment to identify any problems with the monitor system that you will need to be aware of when making your musical decisions.

Listen for Fun but with Intention

Hopefully, we all listen to music for enjoyment. When you hear something that causes a reaction—good or bad—focus your analytical mind for a moment to try to figure out what it is about the sound that you are reacting to. You can easily build up your recognition of instruments and frequency ranges and the feelings you get from different ranges that will guide your productions, mixes, and masters in the future. Honing these skills is part art and part science, but we all can successfully improve our listening skills.

Additional Reading: